Arsenal Interactions and Pitch Tunneling: How Deception Impacts Run Prevention and Wins on the Baseball Field

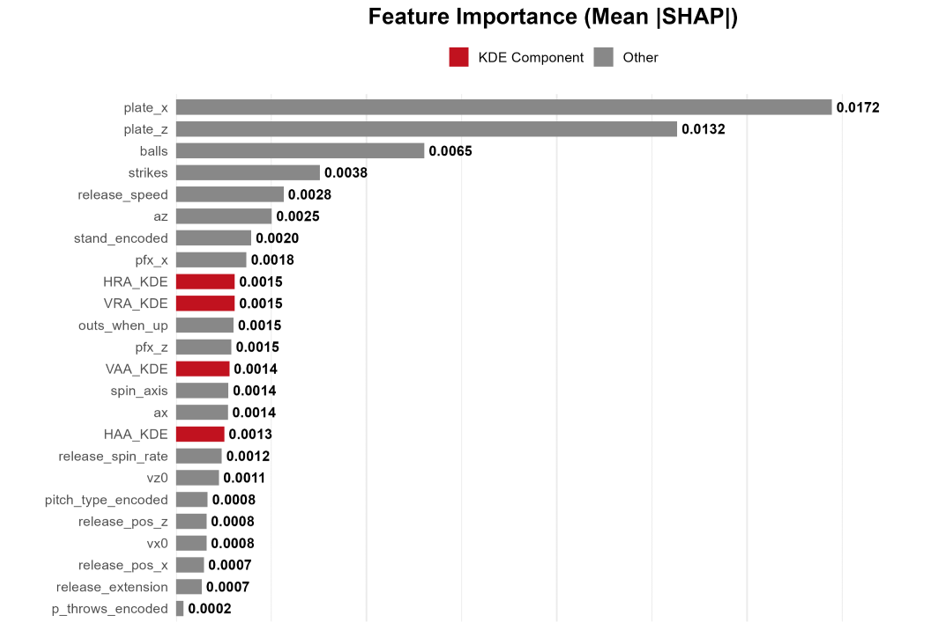

For my thesis, I wanted to quantify the impact of pitch deception and effective tunneling, looking at how specifically pitches interact through release similarity and break divergence rather than evaluating pitch quality in isolation. After cleaning and aggregating all Statcast data from the 2023 through 2025 seasons, and assigning the necessary angle calculations to all pitches, an XGBoost run-value-based model was trained utilizing the engineered tunneling features (VRA_KDE, HRA_KDE, VAA_KDE, HAA_KDE, release similarity, approach divergence). For the KDE values, it measures the density of a distribution at a given value instead of the similarity of two distributions, seeing thus how similar all releases and approaches are to one another. The model gave a stable enough structure in order to extract reliable SHAP contributions. In order to measure how much deception actually influences run prevention, it was necessary to examine the full SHAP feature importance output. Pitch movement, batter stance, spin axis and other physical traits stood between 0.0020 and 0.0014. However, the four tunneling-based kernel-density variables landed in the middle of this meaningful band of features. With HAA_KDE, VAA_KDE, HRA_KDE, and VRA_KDE contributions isolated, each pitcher received a tunneling run prevention per 100 pitches score, which helped to form the basis of a league-normalized metric which I called Tunneling+. Once the Tunneling+ scores were standardized, they could then be aggregated across all pitches thrown by a pitcher in a given year to quantify the full-season impact of their deception or lack thereof in the manner that matters most to teams: wins and revenue. This aggregation allowed for the production of the statistic tWAA (Tunneling Wins Above Average), as well as the rate-based tWAA/162, which was standardized to run prevention over a 2500 pitch sample. In order to create something actionable, as well, utilizing the tunneling-based SHAP contributions, I lagged consecutive pitches to create sequential pitch pair matrices showing which back-to-back combinations prevent runs from tunneling effects alone.

This figure shows the full SHAP importance rankings, indicating that plate_x was the most influential variable (0.0172), with plate_z just behind it (0.0132). This made a ton of sense, as plate_x is the horizontal location of the pitch as it crosses home plate, while plate_z is the vertical location. These two work in conjunction with each other to determine the exact coordinates of where a pitch was located relative to the strike zone. Event/count variables like balls (0.0065) and strikes (0.0038) followed (also makes sense as there are direct run values associated to each of those outcomes), with release_speed (0.0028) and az, or vertical acceleration, (0.0025) rounding out the top quarter of variables that drive run value. Pitch movement, batter stance, spin axis and other physical traits stood between 0.0020 and 0.0014. However, the four tunneling-based kernel-density variables landed in the middle of this meaningful band of features. HRA_KDE landed at 0.0015 gain, VRA_KDE also at 0.0015, VAA_KDE at 0.0014, and HAA_KDE at 0.0013. This shows that these tunneling variables are not simply noise and have actual significance in predicting run value. They sit on the same scale as movement variables and spin-based descriptors, which validates the notion that the model is actually detecting the value of release similarity and approach divergence.

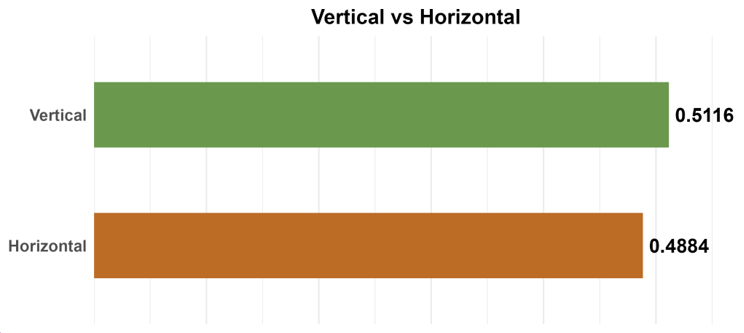

Once SHAP values were fully extracted, the four tunneling-specific variables were isolated and a model was built around them to understand how they actually act when separated from the rest of the features, and, to figure out how much they truly do impact run scoring. As seen in this figure, when grouped by dimension, the vertical contributions totaled 0.5116 of the combined tunneling signal, while horizontal accounted for 0.4884. This split suggests that tunneling deception operates rather evenly in both planes than being dominated by one.

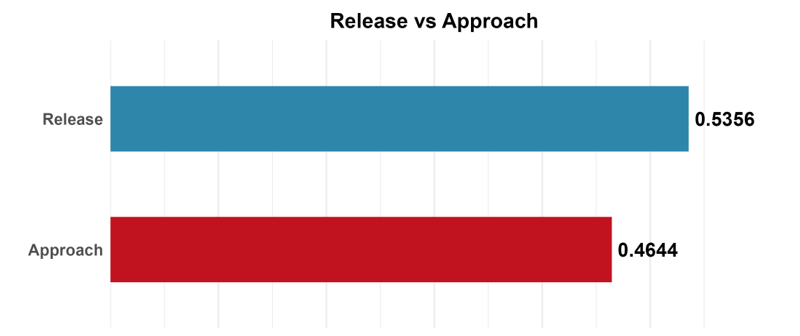

Shown in this figure, when grouped by release and approach, release-based KDE components accounted for 0.5356 of the signal, compared to 0.4644 for approach-based components. Again, while the gap is small, it points to the notion that release similarity contributes slightly more to run prevention than late-stage break alone.

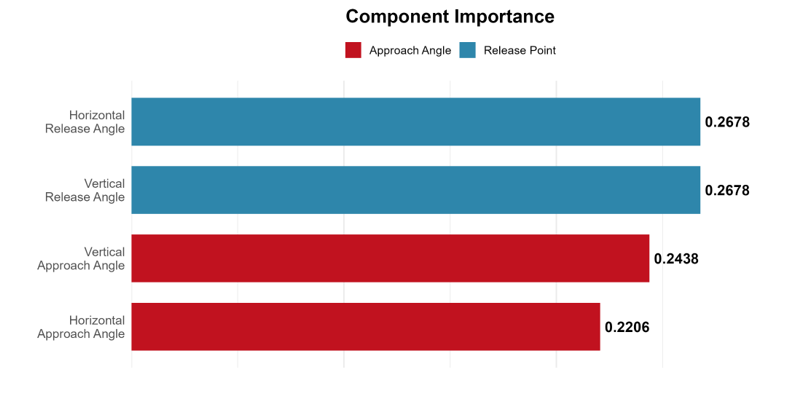

As shown in Figure 4, Horizontal Release Angle (HRA_KDE) and Vertical Release Angle (VRA_KDE) carried identical weights, at 0.2678 each. Vertical Approach Angle (VAA_KDE) followed at 0.2438, and Horizontal Approach Angle (HAA_KDE) at 0.2206. These numbers reinforce the pattern that release and approach each matter, and vertical and horizontal each matter, but none of them dominate to the point of marginalizing the others and truly separating from each other. The effect is closely distributed. Tunneling deception is multi-directional and unfolds over the entirety of the pitch trajectory, and the SHAP values quantify exactly how much each feature moves run value on its own.

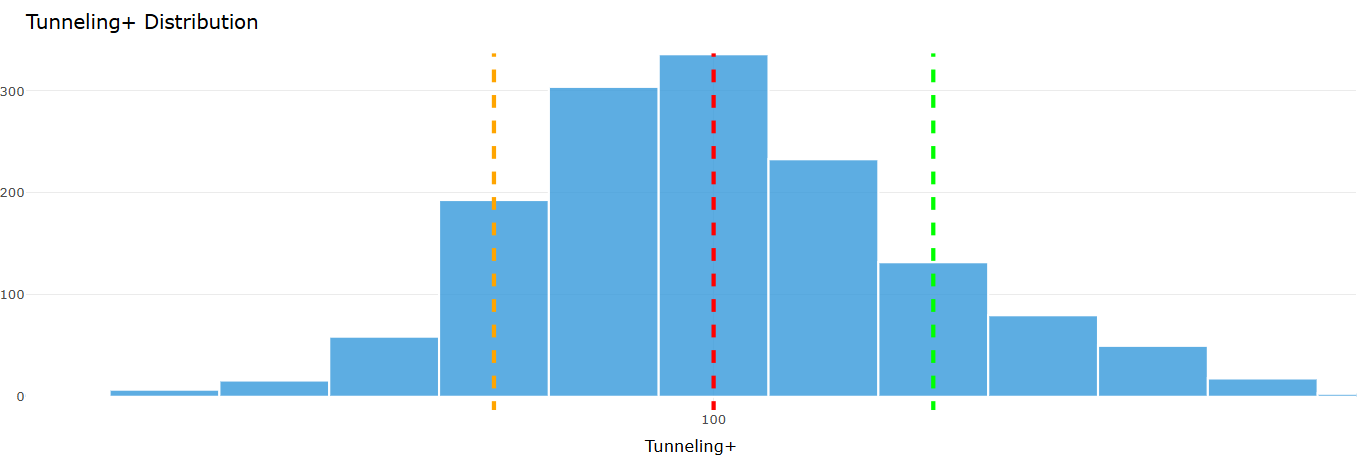

With HAA_KDE, VAA_KDE, HRA_KDE, and VRA_KDE contributions isolated, each pitcher received a “tunneling run prevention per 100 pitches” score, which helped to form the basis of a league-normalized metric which I called Tunneling+, similar to the publicly available Stuff+, Location+, and Pitching+ models. Tunneling+ is centered at 100, with each point (to the hundredth of a whole number) reflecting a normalized increase or decrease in run prevention relative to the league average. This design makes performance much more interpretable at a glance, similar to Stuff+, Location+, Pitching+, wRC+ or ERA+, allowing pitchers with differing workloads to be compared on equal footing on a rate basis. As seen in this figure, a plot depicting the distribution of all scores, all but ten total individual pitcher seasons between 2023 and 2025 fall between 70 and 130 on the scale.

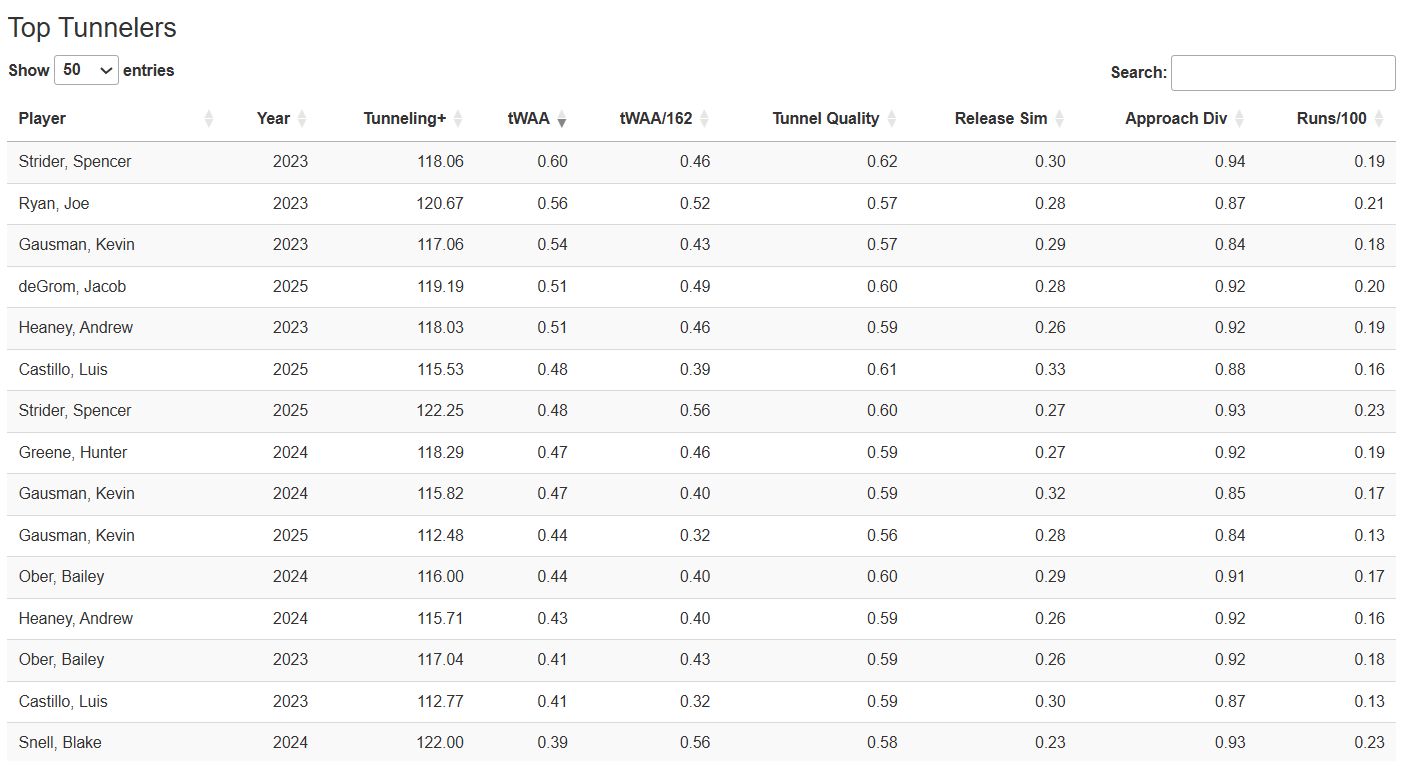

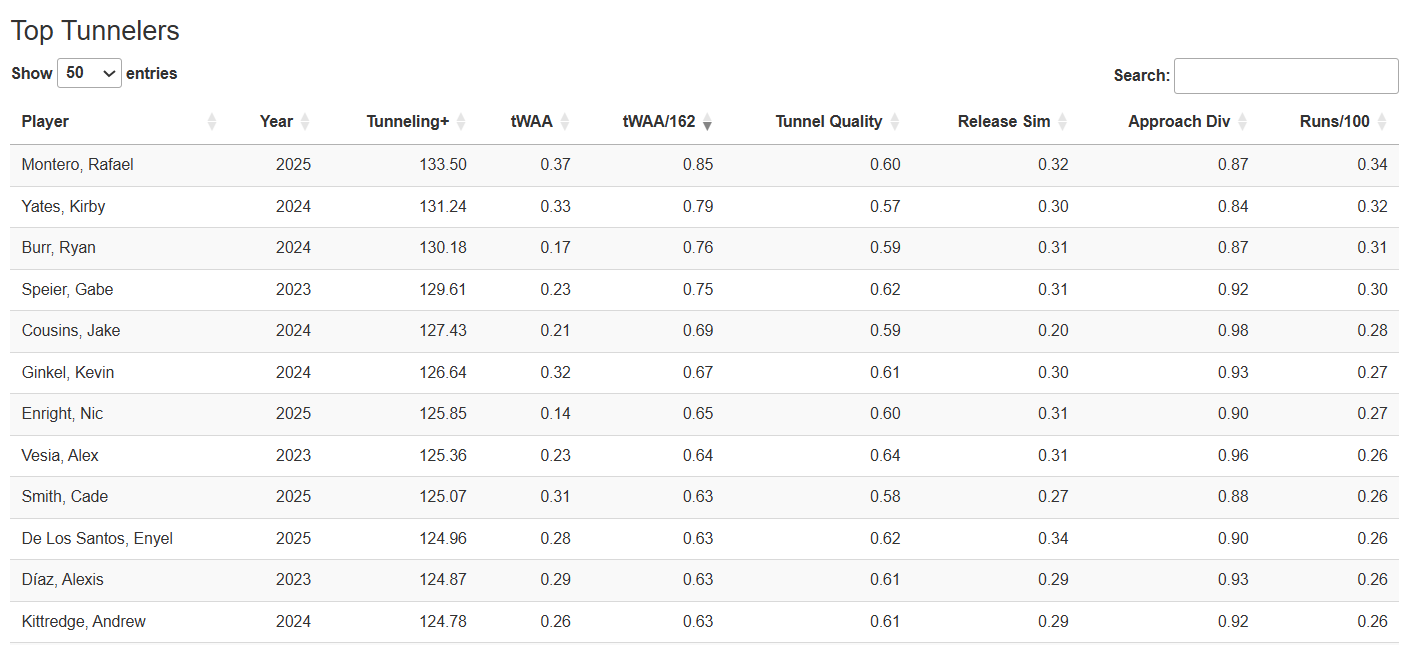

This figure shows the single-season cumulative tWAA leaders (all starters) from 2023 through 2025. The very top seasons in this dataset of 1,442 pitching seasons demonstrate how effective tunneling along can accumulate into real wins over the course of a season. Spencer Strider’s 2023 season was by far the most effective, and deceptive season on record, generating 0.80 tWAA, or four-fifth’s of a win over the full season that saw the Braves win 104 games and clinch the National League’s best record. Joe Ryan and Kevin Gausman’s 2023 seasons followed, at 0.56 tWAA and 0.54 tWAA, respectively, with Jacob deGrom following those three, ranking as the top tunneling season of 2025 at 0.51 tWAA in his first healthy season in this three-year window. While tWAA is effective at capturing the total wins gained through tunneling for full seasons, it gives starting pitchers a serious edge due to their expanded workload over a full season

tWAA/162 was developed as a rate-based version of tWAA that scales each pitcher’s tunneling-driven run prevention to a standardized 2,500 pitch workload, shifting the evaluation from “how many total wins did your tunneling generate this season?” to “how many wins would your tunneling generare over a full, neutralized season?”, which places starters, relievers, and those who lost parts of their seasons to injury on equal footing and isolates tunneling as a skill independent of volume. The rankings of tWAA/162, Tunneling+, and Runs/100 are all identical as they are built on a run prevention rate basis. Tunneling+ captures tunneling value as a normalized index centered at 100, Runs/100 simply expresses it as runs saved per 100 pitches, and tWAA converts those same rate-based effects into wins using the runs-per-win constant of 10. As previously mentioned, Rafael Montero, Kirby Yates, and Ryan Burr ranked as the top three respective individual seasons for Tunneling+, and, those values correspond across the board to tWAA/162 and Runs/100. Montero’s 2025 season (133.50 Tunneling+), led to a 0.85 tWAA/162 and 0.34 Runs/100, both the top ranks across 1,442 individual seasons. Kirby Yates’ 2024 season (131.24 Tunneling+, 0.79 tWAA/162, 0.32 Runs/100), Ryan Burr’s 2024 season (130.18 Tunneling+, 0.76 tWAA/162, 0.31 Runs/100), Gabe Speier’s 2023 season (129.61 Tunneling+, 0.75 tWAA/162, 0.30 Runs/100), and Jake Cousins’ 2024 season (127.43 Tunneling+, 0.69 tWAA/162, 0.28 Runs/100) all follow suit in the same order regardless of which of the three is the focus. They all express the same deception effect on slightly differing scales. A pitcher who tunnels effectively will prevent marginal runs every pitch, and thus, this run prevention leads to a higher Tunneling+ score; and higher Tunneling+ translates over to a higher tWAA/162 once converted through the runs-per-win constant.

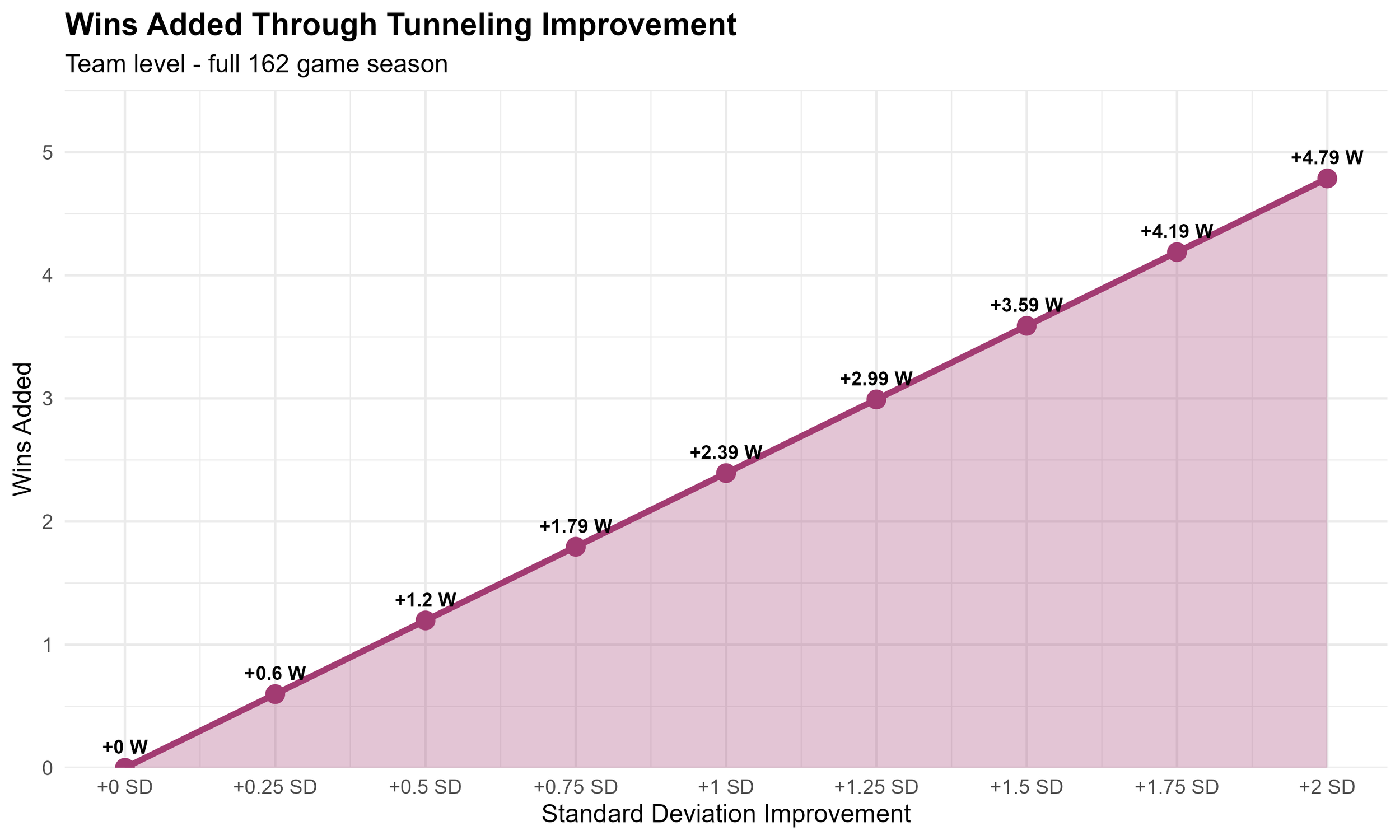

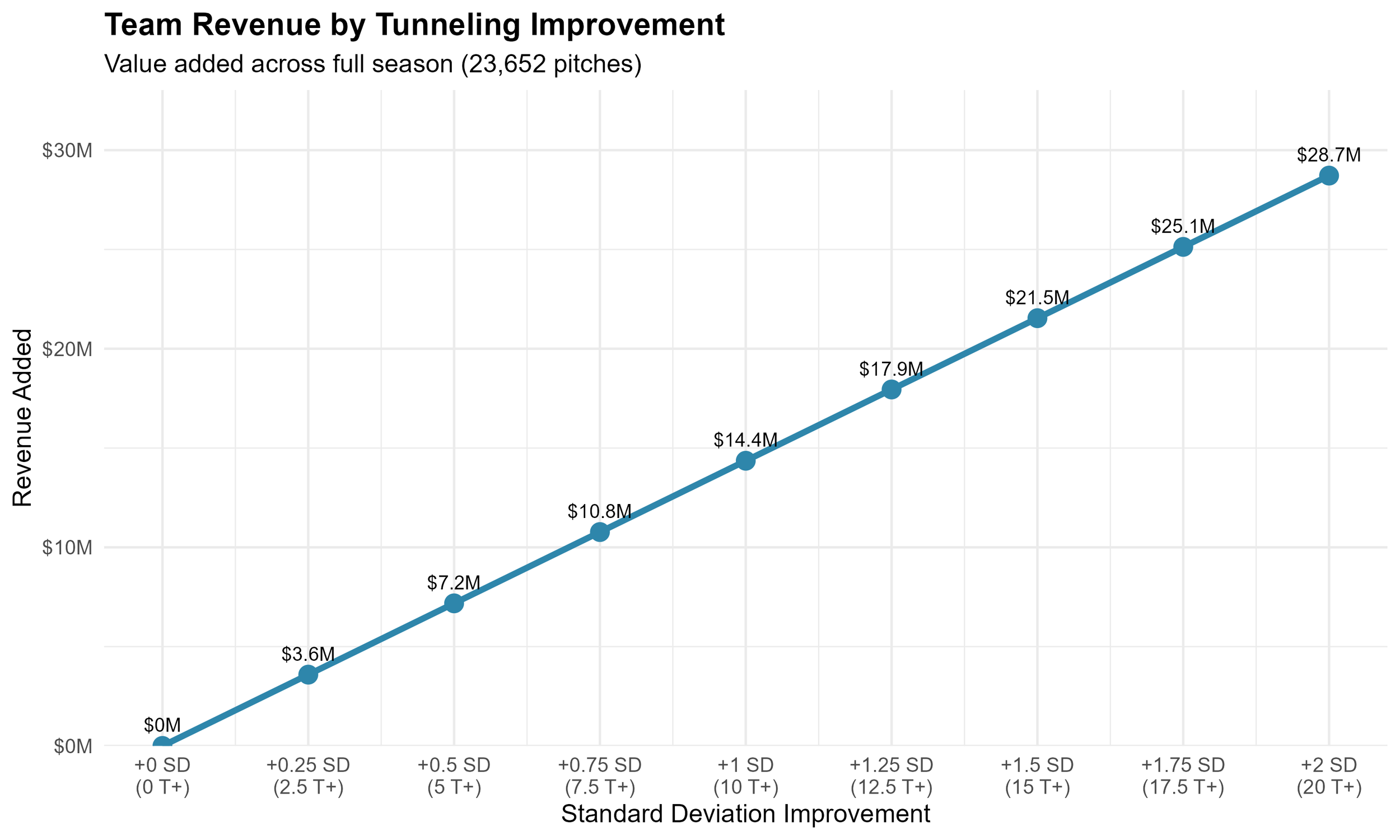

Once the individual pitcher tunneling values were established at both the cumulative (tWAA) and rate (tWAA/162) levels, the next step, was to scale those individual outputs to the team level in order to understand just how much additional value a team could capture by improving their pitching staff’s tunneling profile over a full 162 game regular season. To quantify these improvements meaningfully, the analysis first incorporated the standard deviation of tunneling performance across the league. Before examining total tunneling runs saved, the researcher calculated the standard deviations of each of the four underlying tunneling components and combined them to produce a unified value, reflecting the model’s treatment of tunneling as an additive effect across four independent yet interconnected deception dimensions. Across the 1,442 pitcher seasons, the variance was (in runs prevented per 100 pitches): VRA_KDE (SD=0.059), HRA_KDE (SD=0.063), VAA_KDE (SD=0.047), and HAA_KDE (SD=0.052). These individual spreads show how much each pitcher differs in each phase of this tunneling window, so to speak, between release and approach, and on the vertical and horizontal planes, helping to illustrate why tunneling is an accumulated effect. When combined, the total tunneling SD was 0.101 saved per 100 pitches (then scaled to 10 point SDs in Tunneling+), which then served as the foundation for team-level scaling. Because every pitcher-season in the dataset is captured on a per-pitch run prevention estimate, the logical way to scale this up to a full team season would be to find the average number of pitches that a team throws per game, and multiply that by 162. After reviewing the full Statcast dataset covering the last three seasons, the average number of pitches thrown per team per game was found to be approximately 146. Using this baseline, the standardized tunneling effects, expressed as runs saved, were scaled proportionally to a 23,652 pitch workload to estimate how many wins a team would gain by improving its overall tunneling performance. To make this interpretable, team tunneling performance was standardized at 0 (0 runs saved), and modeled a series of improvements quarter-SD increments, going from 0 SD up through +2 SD. This allowed for the answering of the question: “How valuable would it be for a team to improve their deception?” By taking the 0.101 runs-per-100-pitch standard deviation and projecting it across a full 23,652-pitch regular season, each partial-SD improvement was converted into corresponding win totals using the same 10-runs-per-win constant established earlier on. This figure visualizes this relationship. A +0.25 SD team-wide yields roughly +0.60 wins per season, then, at +0.5 SD, a team gains 1.2 wins per season, then, at +0.75 SD, a team gains 1.79 wins, and, if a team’s staff improved by a full SD, they would see an improvement of 2.39 wins over an entire season. The subsequent steps continue in this linear pattern, with +2.99 wins at +1.25 SD, +3.59 wins at +1.5 SD, +4.19 wins at +1.75 SD, and a peak of +4.79 wins at +2 SD. What this illustrates is that tunneling-driven run prevention, when scaled to a team volume compounds linearly, turning small pitch-level effects over the course of an entire season.

Once the win totals were established, the next step was to convert these incremental win values into financial equivalents. In MLB, teams already use marginal-win valuation internally when modeling out their roster and when conducting player valuation, and these numbers differ per the size of the market. Vince Gennaro of SABR (Society for American Baseball Research) published an article Estimating the Dollar Value of Players provided a framework to work off of. In his examination of free agent contract and the relationship between salary and player value, Gennaro finds that, per win, teams have effectively paid about $6 million once performance is converted into WAR and normalized for era-specific conditions. Another study, conducted by Lauren G. Walker, analyzed MLB financial data and found that incremental wins reliably increase team revenues finding that the average marginal win is worth roughly $2.7-$2.8 million, but this value differs drastically dependent on market size. Her study found that teams like the Yankees, Mets, and Dodgers, who play in the two biggest markets in the country, value a win anywhere from $14-$20 million, while these small market teams fall lower in that $1-$2 million range (Walker, 2025). Using this framework, the tunneling-driven win estimations were converted into revenue by applying the methods from both Gennaro and Walker, settling on a universal mid-point value of $6 million per team win. This figure utilizes that number, converting the tunneling-driven win values into revenue across an entire season, broken down into quarter-SD increments akin to the runs-to-wins model. At a +0.25 SD improvement, the marginal revenue is roughly $3.6 million, while a +0.5 SD improvement can lead to a $7.2 million increase in revenue. A +0.75 SD improvement nets a team $10.8 million, while a full SD improvement from their entire pitching staff will generate a team roughly $14.4 million over an entire season of 23,652 pitches. These numbers illustrate that the same marginal improvements in wins due to runs saved from tunneling can scale rather cleanly into eight-figure revenue gains in a given season. If a team can add on two to five wins purely through improved deception, something that does not require a major player acquisition, solely developmental refinement, the financial upside is enough to matter.

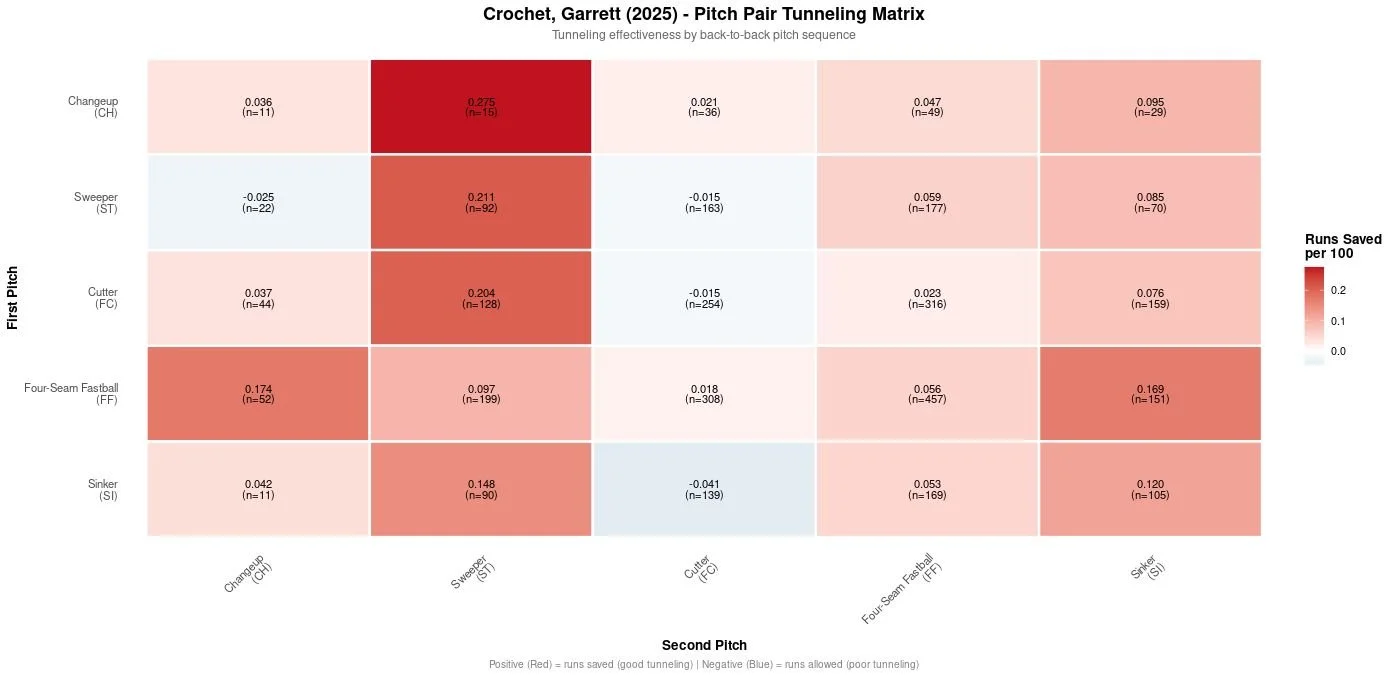

Once the team-level wins and revenue implications of deception were established, the model needed to be pushed further, from understanding how good a pitcher’s tunneling is in the aggregate into something that is actionable, by figuring out which pitches tunnel best sequentially, which is information that could in fact aid in-game strategy. A sequencing layer was built on top of the SHAP outputs treating every back-to-back pitch as a distinct event, thus asking how much tunneling value that the pair generated by xRV. Using the full pitch-level dataset, things were collapsed down to the pitch type space, by grouping by the variable pitch_type, and summarizing the average tunneling runs saved as well as each of the four component contributions. Then, the sequencing part started when pitches were re-indexed within each pitcher year and carry the previous pitch’s type and tunneling contribution forward using lag(), so every row in pitch_pairs now has both a prev_pitch_type and a current pitch_type, along with their SHAP-based tunneling value and a readable label like “FF to SI”. After filtering out the first pitch of every season, that produced several million back-to-back sequential pairs, which were then grouped by (prev_pitch_type, pitch_type) and then averaged the tunneling contribution again for each pair. By isolating which back-to-back pitch transitions preserve deception for a given arm, and which ones break the tunnel, coaches and front offices can script sequences to maximize confusion, avoid patterns that hitters pick up on, and tailor in-game adjustments to the pitcher’s actual tendencies, making this matrix an actionable blueprint for how a pitcher can sequence their arsenal to extract the most deception in game.